The Idea for a Memorial and Sir Edwin Lutyens

By 1923, the Memorial Committee was well established, the funds raised, and the books compiled and published, but a location and design for an actual memorial was proving difficult to pin down. The initial idea, back when the committee had been formed in 1919, was for a Memorial Home, which would provide lodging to soldiers passing through Dublin. As independence grew more likely, this Home scheme grew less probable. Two more main proposals were considered, and then rejected, by the new Irish Government of the time. The first was a monument in Merrion Square, and the second a new commemorative entrance archway to the Phoenix Park (similar to the one which had been recently erected in St Stephen’s Green).

The idea to purchase Merrion Square (then a private facility for the residents of the nearby houses), erect a memorial monument within, and then open the square to the public, was first floated in 1924. Over two years of different applications, injunctions, and government-level discussions, the Committee realised that it would not go ahead. There were many reasons for this. Some supporters felt that the funds raised should go towards a facility which would provide practical aid to the thousands of war veterans in the country at the time. More felt that Merrion Square was far too small a location for the huge crowds that the annual Armistice Day celebrations attracted. The government felt that the financial commitment to maintaining a new public park was not something the Irish budget could extend to at that time. There were passionate protests from some living on Merrion Square itself, particularly from John Sweetman whose influential letter to The Leader newspaper argued against the idea of “a perpetual memorial park in honour of some deceased Irish soldiers of the English Army”. The Bill was eventually withdrawn in April 1927, following a debate where Kevin O’Higgins said that “…there will always be respectful admiration in the minds of Irishmen and Irishwomen for the men who went out to France and fought there and died there, believing that by so doing they were serving the best interests of their country… yet it is not on their sacrifice that this State is based and I have no desire to see it suggested that it is.”

In 1928, the idea of a memorial arch as a new entrance to the Phoenix Park was brought to government, who only took four months to decide against the proposal this time. Those in favour of a the Phoenix Park location thought it would handle the Armistice Day crowds more successfully; those against (this included Andrew Jameson of the Memorial Committee) thought that a monument so far from the city centre would not be seen by many people.

In 1929, Jameson contacted Liam Cosgrove, President of the Executive Council (essentially Taoiseach), to seek an end to the matter. Cosgrove invited his ministers to contribute ideas, but nothing useful was forthcoming. Jameson decided instead to ask Cosgrove to allocate a portion of land in the Phoenix Park, instead of the entranceway itself. Cosgrove then asked the Office of Public Works if there were any lands adjacent to the Phoenix Park that might be suitable, and he specified the strip of land between Conynham Road and the river (this is the area occupied by the sequence of boat and rowing clubs today). The OPW replied that that land was unsuitable, but that a nearby site may be suitable.

It was at this junction that T.J. Byrne, Principal Architect with the OPW, became involved. It was his suggestion that the Long Meadows Estate, directly across the river from the Phoenix Park, would facilitate a memorial. Long Meadows had been under the administration of the OPW for about thirty years at this stage, and consisted mainly of allotments. If any of the Memorial Committee were reluctant to accept the arrangement that Jameson and Cosgrove had come to, the promise of extra funds from the government (because of the inclusion of a public park) allayed their concerns.

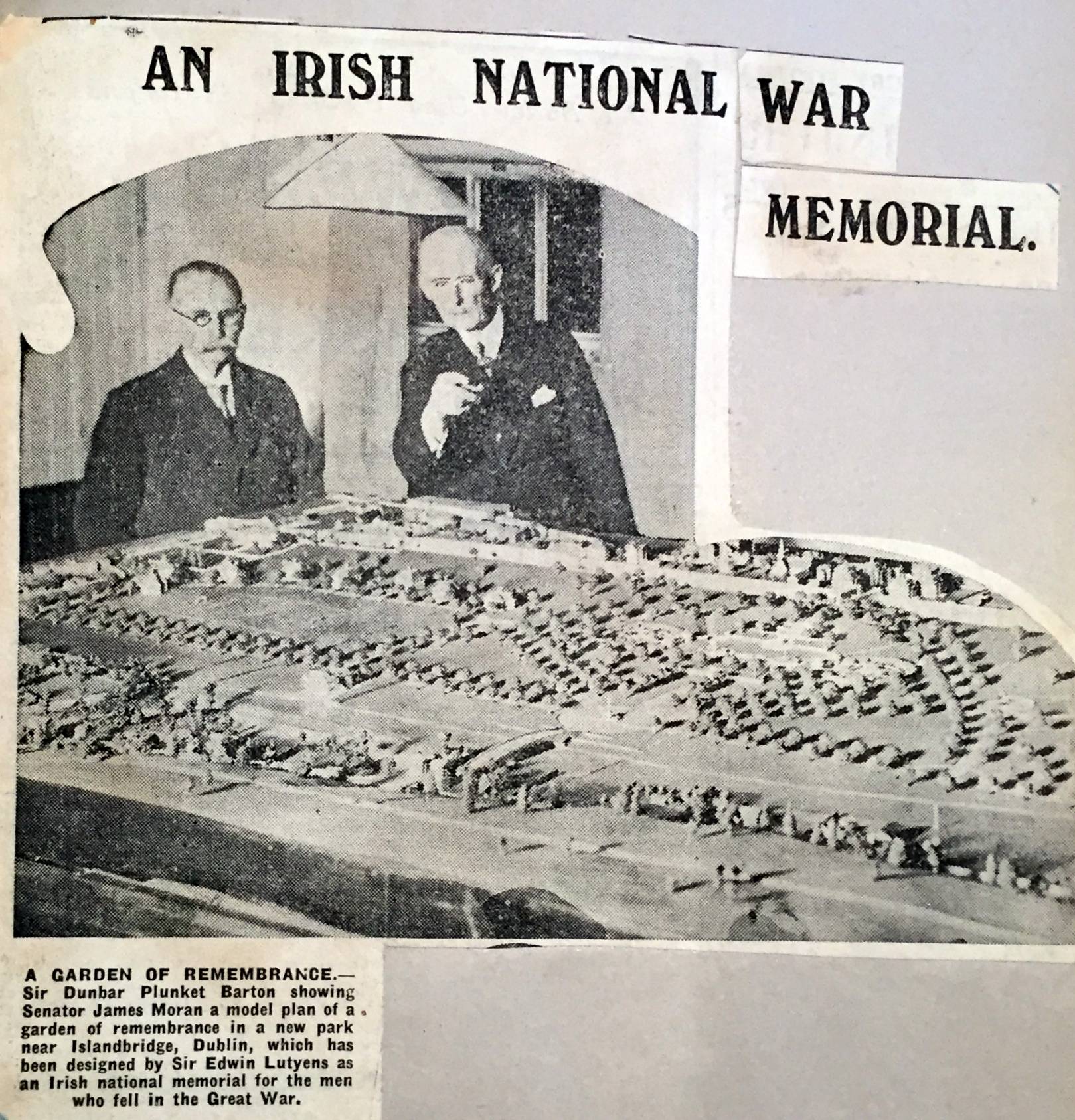

It was at this point that Jameson revealed that he had been in talks with Sir Edwin Lutyens, probably the most prominent architect of the period, with a view to commissioning a design for the Irish National War Memorial Gardens. In late summer 1930, Lutyens came to Ireland and saw Long Meadows for the first time. He also met Cosgrove, who was suitably impressed by his reputation. Lutyens prepared a design, which was forwarded to T.J. Byrne, who compiled a lengthy report and estimate of cost. Byrne recommended it to the Government in November, where it was approved, and a scale model commissioned. This was approved in July 1931. There were two parts to Lutyens’ design – a memorial garden and a connecting bridge to the Phoenix Park. The latter was abandoned due to lack of funds at the time.

Sir Edwin Lutyens was born in London in 1869 to Captain Charles Lutyens and Mary Gallwey. Mary was from Cork, and had met Charles through her brother, who had served with him. They married in Montreal in 1852. Edwin was the tenth of their thirteen children. After attending Kensington School of Art, Edwin set up his own architectural practice at the age of nineteen.

In 1918, Lutyens was one of three architects appointed by the Imperial War Graves Commission (now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) to design cemeteries and memorials for those who had lost their lives in the First World War. The other two architects were Sir Herbert Baker and Sir Reginald Blomfield; together, the three formed a formidable team as the most respected architects of their day. The commemoration of war dead after the First World War was very different to how it had been before. Because of the sheer scale of loss in that war, and the involvement of men and women from all classes and all villages, individual remembrance became expected. Each dead serviceman was to be recognised, and every location in Britain which had lost men were to commemorate them by memorial.

The primary national war memorial in the U.K. is the Cenotaph in Whitehall, London, and was given this designation in 1920. It had been designed by Lutyens in 1919. The cenotaph (‘empty tomb’) was intended as a memorial for those whose bodies lay elsewhere. Within England alone, Lutyens designed forty-four war memorials. In 1929, Lutyens was also responsible for the design of one of the most famous memorials in northern France – the Thiepval Memorial. This monument commemorates over 72,000 soldiers who remained missing after the Battle of the Somme; each of their names is inscribed on stone panels. The Stone of Remembrance, an enormous altar-like stone which appears in all commemorative or cemetery sites which honour more than a thousand war dead, was also of Lutyens’ own design.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, Lutyens worked in Ireland at Howth Castle and Lambay Island, providing those sites with architectural extensions and interior refurbishment. In 1912 the gardens at Heywood, Co. Laois were completed. These gardens are also in the care of the Office of Public Works today.

It was among this context that Lutyens was approached to create a memorial at Islandbridge in 1931. These Gardens were to become Lutyens most famous work in Ireland, and are internationally recognised as a significant example of memorial landscape architecture.