The Books of Remembrance and Harry Clarke

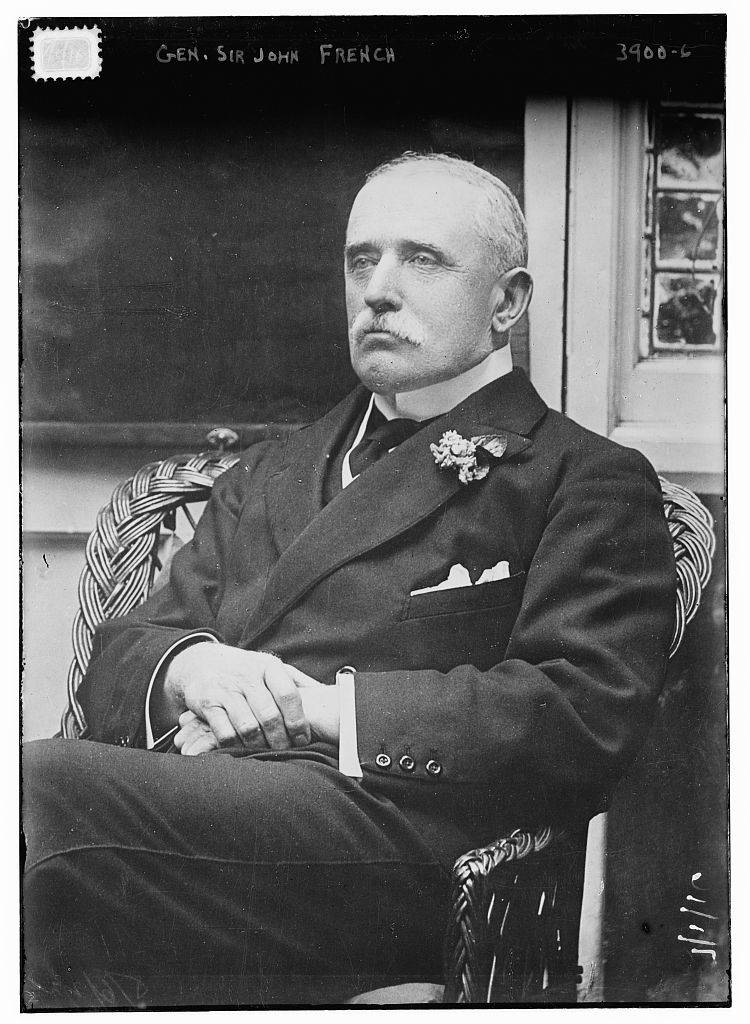

Two weeks after the Treaty of Versailles was signed, in July 1919, a meeting was held in the Vice-Regal Lodge in the Phoenix Park, Dublin where it was decided to establish a war memorial to commemorate the Irish war dead. Over a hundred people, from across the country, attended this meeting, which was chaired by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland at the time – Sir John French, Earl of Ypres. A Memorial Committee was appointed in order to raise the funds that were needed. The Standing Committee, which met regularly, and which steered the efforts from August 1919, consisted of:

- Sir Dunbar Plunket Barton, 1st Baronet PC (Chair) (1853-1937)

- Andrew Jameson, PC (Ire) DL (Treasurer) (1855-1941)

- Dame Caroline Sydney Williams Arnott, DBE, OStJ, JP (d.1933)

- The Rt. Hon. Francis “Frank” Brooke, PC, JP, DL (1851-1920)

- Lt. Col. John Steele, OBE, DCM

- Mr Lewis Beatty (Co-Treasurer)

- Alderman James Moran, JP

- Vivian Brew-Mulhallen

- E. Saunderson

- E. White

- Mr Justice Henry Hanna K.C. (1872-1946)

- Major Gen. Sir William Hickie, KCB (1865-1950)

An initial £50,000 was raised through public donation. While different locations and settings for a permanent war memorial were suggested and rejected over the next decade, the Memorial Committee set about commissioning an interim project. This was to be a set of books, the pages of which listed the names of every Irish soldier who had been lost in the war. The books were compiled, designed, and produced during one of Ireland’s most turbulent periods – during the War of Independence (1919-1921) and the following Civil War (1922-1923) – before being finally published in 1923.

A subcommittee was formed and given the task of collecting names for the books. One member was Sergeant Hanna who spoke, on behalf of the subcommittee, to the Irish Press in December 1922. There were issues from the very beginning about what ‘Irish’ meant in terms of who would be included, and what sources would be used in order to collect the most accurate information.

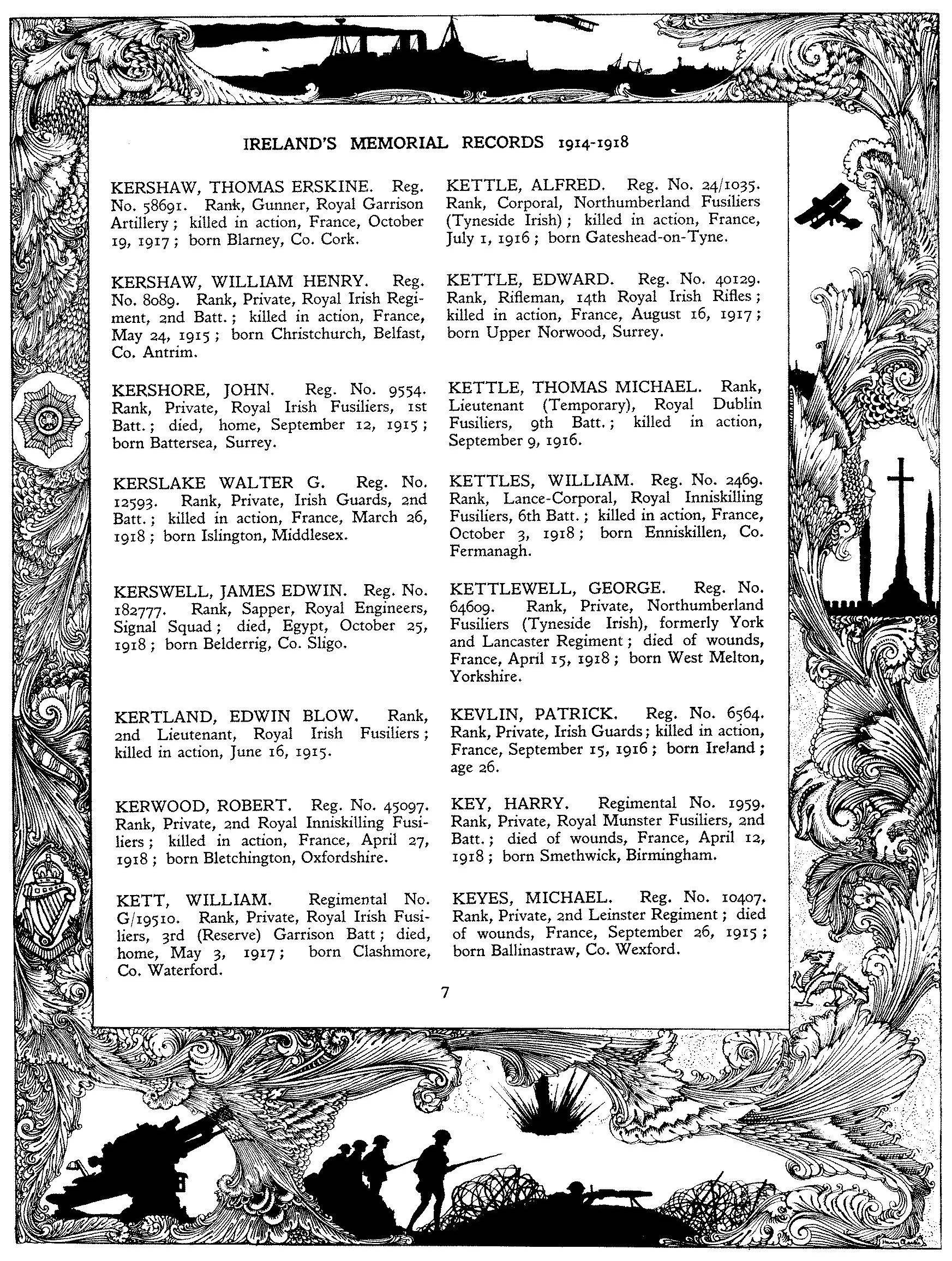

This list ran to just under 50,000 names, occupying 3,200 pages over eight volumes altogether. The very best of Irish artisans were involved in the production, the cost of which ran to £5,000. The paper on which the names were printed had been handmade by Maunsel and Roberts Ltd, Dublin. The binding, with grey paper boards and a linen spine for most of the editions, was carried out by Galway & Co. Binders, also of Dublin.

Harry Clarke, already very well-known and highly-regarded for his work in book illustration and stained glass, was commissioned for the border decoration. He created seven different designs which were repeated and reversed throughout the set, a front page, and a last page (sixteen different arrangements in total). Silhouettes of military scenes are mixed with drawings in black ink from Celtic mythology to form a setting for each page that was uniquely of its time. The items silhouetted are very specific to the Irish experience of the First World War. It is possible to identify, for example, the badge of the Royal Irish Rifles, the Blomfield Cross of Sacrifice, Sulva Bay, searchlights, and even a broken spur. Two companies were responsible for the engraving of the illustrations – The Irish Photo Engraving Company and The Dublin Illustrating Company.

One hundred copies of each book were printed, the idea being that every library of note would hold one in its catalogue. The full list of recipients of the books has not survived. Recent research has located 35 of the 100 surviving sets, as well as a valuable list of institutions which do not hold any copy.

The books were digitised in CD-Rom form in 1995 by Eneclann Ltd of Dublin. A paper version was republished by the Naval and Military Press in the U.K. and laid at the base of the Irish Peace Tower in Messines. In 2014, the books were made searchable online, through a new digitisation effort which was a collaboration of Google, the In Flanders Fields Museum (in Ypres, Belgium), and the Irish Dept. of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

When the gardens were completed, each of the four bookrooms held a pair of books from the set. Today the full set is displayed in the south-east bookroom. The north-east bookroom contains the digital (CD-Rom) version, and members of the public have the opportunity to search the Records and print out any page. The books are widely used as a reference work by historians and genealogists. They are also used in commemorative ceremonies. From 2012 to 2015, the eight volumes held in the Irish National War Memorial Gardens were conserved by Marsh’s Library, Dublin. Conservation included cleaning, paper reinforcing, and relining.

Ireland’s Memorial Records have the effect of humanising the losses of the war, something difficult to achieve because of the sheer scale. They detail the name, rank, and regiment of each soldier, but also their age, how they died, and where they had been born. For some men, this was their only memorial, whether because their bodies had not been recovered, or because there were political difficulties with the placement of appropriate headstones locally. Of the almost-50,000 men commemorated in these lists, around 30,986 were born in Ireland. The remaining were born elsewhere but considered themselves of Irish heritage. 4,800 were Dubliners.

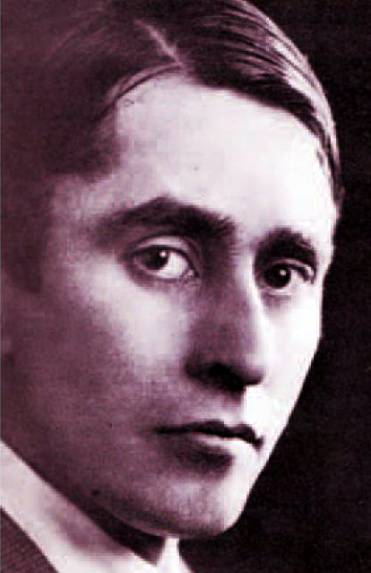

Born in Dublin in 1889, Harry Clarke grew up in 33 North Frederick Street, with his father’s decorating and stained glass business occupying a workshop to the back of the house. Harry became apprenticed to this business at the age of fourteen, following the death of his mother. His work in stained glass soon began to win awards, beginning with the Board of Education (London) gold medal at the age of twenty-two. His first forays into the world of book illustration came about two years later, and his illustrated Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Anderson was commissioned in 1913 (published 1916). His reputation as a book illustrator grew with each new commission, and his work was widely admired. It was among this context that he was asked to illustrate Ireland’s Memorial Records, which was published in 1923. His work for the Memorial Committee impressed many with its sombre, sensitive, and poignant tone.

It was two years after this that he created possibly his most controversial work, the Geneva Window. This was to be a panoply of Irish writers which the Irish Government were planning to present to the League of Nations. The inclusion of what President Cosgrove called a ‘scantily-clad female’ in one of the panels caused enough concern that the window was never presented in Geneva. Discussions with the studio about changes which could be made to the window design dragged on for an number of years, never reaching resolution. It was during these protracted delays that Harry Clarke died in the Swiss town of Chur in 1931, on his way home from time spent at a sanatorium in the Alps. He was only 41.

It is with very deep regret that this Academy records the death on the 6th of January of Harry Clarke, R.H.A. In the passing of Harry Clarke, Ireland has lost an artist of rare distinction and the Academy a highly valued member. Examples of Harry Clarke’s work in stained glass are to be seen not in Ireland only but in many places abroad. As a book illustrator he gave his abundant fancy full rein, and in this, as in all his work, the teeming fertility of his imagination is manifest.