Learn More

Background History

Following a meeting of over one hundred representatives from all parts of Ireland, held in Dublin on 17th July 1919, it was agreed that there should be a permanent memorial to commemorate all those Irish men and women killed in the First World War, and a Memorial Committee was appointed to raise funds to further this aim. A number of schemes were suggested, including a memorial centrepiece in Merrion Square, but all were found to be impractical or inconsistent with legal obligations. The matter had arrived at an impasse, until, in 1929, the Irish Government suggested that a Memorial Park be laid out on a site known as Longmeadows on the banks of the Liffey. The scheme embodied the idea of a public park, to be laid out at Government expense, which would include a Garden of Remembrance and War Memorial to be paid for from the funds of the Memorial Committee. Construction of the linear parkway, about 60 hectares in extent stretching from Islandbridge to Chapelizod, began in 1931 and took about two years to complete. The Memorial Gardens were laid out between 1933 and 1939. The workforce for the project was formed of fifty percent of ex-British Army servicemen and fifty percent of ex-servicemen from the Irish National Army.

The Landscape Designer

Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944), the distinguished British architect and landscape designer, was commissioned to prepare the design. Lutyens was no stranger to Ireland having previously worked on Lambay Island, Co. Dublin, for Lord Revelstoke, at Howth Castle for T.J. Gainsford-St Lawrence, and at Heywood, Co. Laois, for Colonel and Mrs Hutcheson Poë. Heywood is now managed by the Office of Public Works. The gardens as a whole are a lesson in classical symmetry and formality and it is generally acknowledged that his concept for the Islandbridge site is outstanding among the many war memorials he created throughout the world. His love of local material and the contrasting moods of the various ’compartments’ of the gardens, all testify to his artistic genius.

The Central Lawn

The central ‘compartment’ consists of a lawn enclosed by a high dry limestone wall with granite piers. In the centre is the ‘War Stone’ of Irish granite, symbolising an altar, which weighs seven and a half tons. The dimensions of this are identical to War Stones in First World War memorials found throughout the world. The War Stone is flanked on either side by broad fountain basins, with obelisks or ‘needles’ in their centres symbolising candles.

On rising ground south of the War Stone, at the head of a semi-circular flight of granite steps, stands the Great Cross with its truncated arms. This is aligned with the War Stone and central avenue. On the cope of the wall at the cross is inscribed the words “To the memory of the 49,400 Irishmen who gave their lives in the Great War, 1914-18”. The original main entrance to the gardens was to be have been from the south where the bridge over the railway line was designed to carry elaborate colonnades of chiselled granite, but this was never completed.

At either end of the lawn are two pairs of Bookrooms in granite, representing the four provinces of Ireland. These contain the Books of Remembrance in which are inscribed the names of the 49,400 Irish soldiers, who died in the First World War. These books contain illustrations by the celebrated Harry Clarke. One of the bookrooms now houses the Ginchy Cross, a wooden cross of celtic design, some 13ft (4m) high which was erected in 1917 as a memorial to the 4,354 men of the 16th Irish Division who died in the two engagements at Guillemont and Ginchy during the 1916 Battle of the Somme. Later replaced by a stone cross, the original cross was brought back to Ireland in 1926.

The Sunken Rose Garden

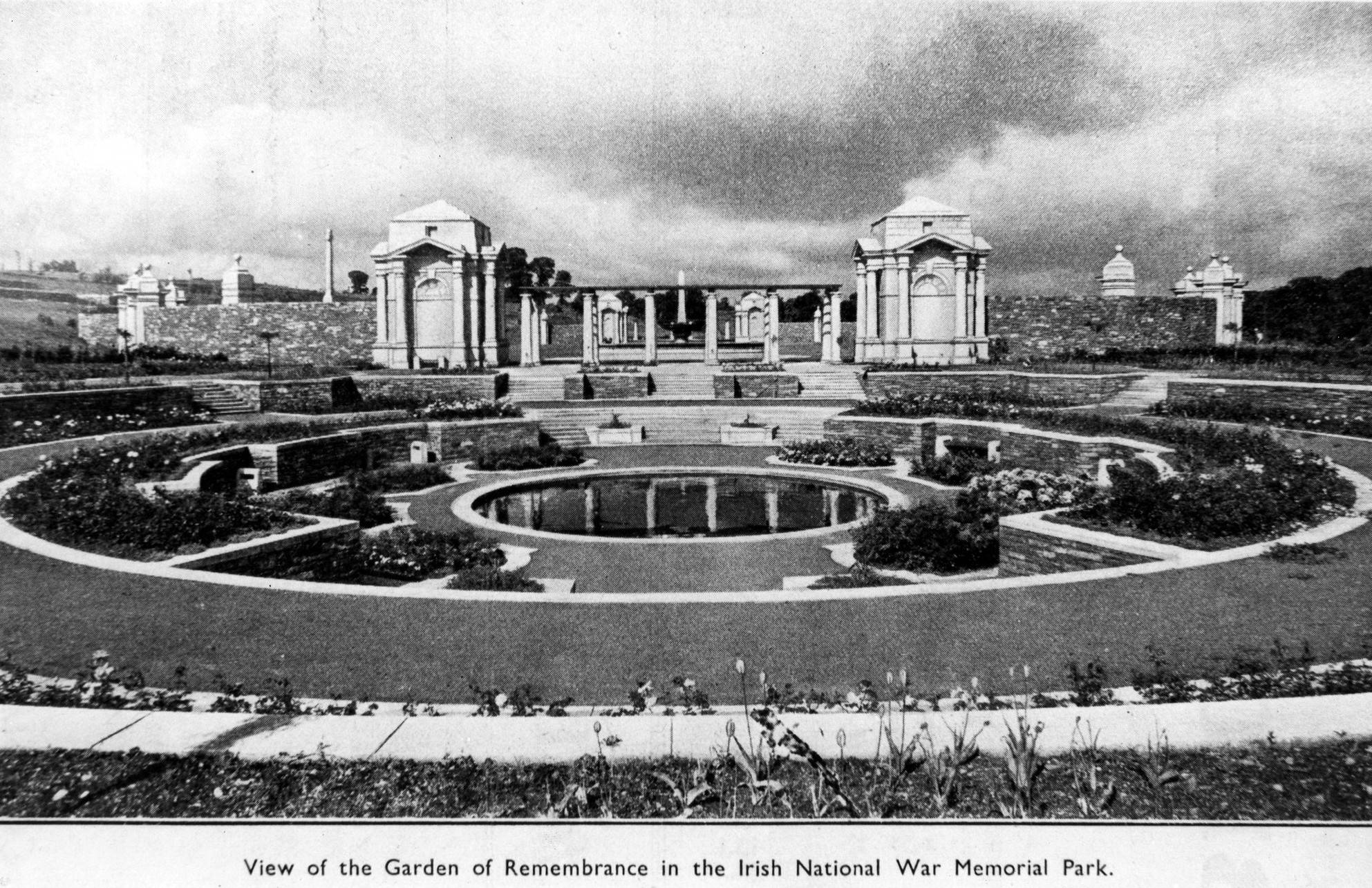

On either side of the central green lawn, through pergolas of granite columns and oak beams, are the sunken rose gardens. These have central lily ponds as focal points and are encircled by yew hedges. Apart from the obvious symbolism of death and resurrection as represented by the ‘altar’, ‘candles’ and cross, Lutyens set out to create a tranquil memorial garden devoid of all military symbolism. It has been suggested, though, that the sunken rose gardens were inspired by the Roman arenas for gladiatorial combat and that the pergolas clothed in clematis and wisteria are reminiscent of places of rest for the wounded combatants.

The original rose varieties, purchased in multiples of fifty, included popular varieties such as ‘Shot Silk’, ‘Madame Butterfly’, and ‘Etoile de Hollande’. In the recent rejuvenation of the rose beds it was considered appropriate to include the famous ‘Peace’ rose produced by Meilland of France in 1945. However, it is planned that, in time, the existing roses will be replaced with the original varieties.

Download

A guide to the archaeology of the Gardens.

The North Terrace

Eight holly trees originally stood as ‘generals’ on the North Terrace overlooking serried ranks of flowering cherries or ‘foot soldiers’. The formality of the lines of Prunus ‘Ukon’, ‘Hisakura’ and ’Watereri’ contrasts boldly with the informality of the parkland trees beyond, which were chosen to give variety and colour, seasonal interest and contrasting form. It is worth noting the landscape impact created by sixty-year-old Atlantic cedars, purple beeches, evergreen oaks, silver birches, whitebeams and scarlet hawthorns at Islandbridge.

The Avenues

A series of tree-lined roads and paths radiate from the central dome-shaped temple. In Lutyen’s original design, each of these was to have focused on a particular landscape feature.

The formality of these paths and roads is reinforced by the judicious choice of trees to give a series of avenues of contrasting form, colour and height. The outer Horseshoe Road was planted with a single line of silver limes. Two diagonal avenues were planted with golden poplars. Magnificent elms once adorned both the central avenue and the two short avenues which join the sunken rose gardens with the diagonal avenues. Unfortunately, these succumbed to Dutch elm disease in the early 1980s. These have now been replaced with lime trees. The lower avenue, which runs at right angles to the central avenue, was planted on each side with Norway and silver maples.

Sixty years of storms have, however, taken their toll on the splendour of these avenues and have been especially hard on the golden poplars and, to a lesser extent, the silver maples. The two avenues of golden poplar were replanted in early 1998.

The Planting Schemes

The planting schemes were, in Lutyens’ view, of vital importance to the success of the overall design. His proposals were implemented by a committee composed of eminent horticulturists, including Sir Frederick Moore, the former keeper of the National Botanic Gardens. The assistant superintendent of the Phoenix Park, Mr A.F. Pearson, was also on the committee and he supervised the planting of trees and shrubs by the Phoenix Park Forestry Unit as well as selecting the four thousand roses for the sunken rose gardens.

The Recent Past

A combination of pests, diseases, weather and natural decay, coupled with the lack of staff in the late 1960s, all conspired to reduce the Memorial Gardens to dilapidation. Restoration Work undertaken by the Office of Public Works commenced in the mid-1980s and is now completed. This was jointly funded by the government and the National War Memorial Committee, which is representative of Ireland, both north and south. On 10th September 1988, fifty years after were initially laid out, the Gardens were formally dedicated by representatives of the four main Churches in Ireland and opened to the public. The Irish National War Memorial Gardens are now managed by the Office of Public Works in conjunction with the National War Memorial Committee.

Bibliography

- D’Arcy, Fergus. Remembering the War Dead (2007)

- Geurst, Jeroen. Cemeteries of the Great War by Sir Edward Lutyens (2013)

- Gordon Bowe, Nicola. Harry Clarke: the Life and Work (2012)

- Johnson, Nuala C. Ireland, the Great War, and the Geography of Remembrance (2003)

- Reynolds, David. The Long Shadow (2013)

Genealogy

Trace your military ancestors with the help of these resources.

- Ireland’s Memorial Records

- Irish Genealogy

- Genealogical Society of Ireland, especially this invaluable guide (PDF)

- The 1901 and 1911 Census Online

- Griffith’s Valuation Records

- Family Search (contains Irish civil records index)

- Roots Ireland

- Ancestry, especially their WW1 search

- The Irish Military Archives

- Irish Casualties of World War One on Ancestry

Pedestrian Gate

Pedestrian Gate

Temple

Temple

The plaque on the floor reads: “We have found safety with all things undying / The winds, and morning, tears of men and mirth / The deep night, and birds singing, and clouds flying / And sleep, and freedom, and the autumnal earth.”

Public Carpark

Public Carpark

Pedestrian Gate

Pedestrian Gate

North Terrace

North Terrace

Eight holly trees originally stood as ‘generals’ on the North Terrace overlooking serried ranks of flowering cherries or ‘foot soldiers’.

Rose Garden

Rose Garden

The sunken rose gardens have central lily ponds as focal points and are encircled by yew hedges.

Rose Garden

Rose Garden

The sunken rose gardens have central lily ponds as focal points and are encircled by yew hedges.

Bookroom

Bookroom

The four granite bookrooms, representing the four provinces of Ireland, contain the books of remembrance as well as the Ginchy Cross.

Bookroom

Bookroom

The four granite bookrooms, representing the four provinces of Ireland, contain the books of remembrance as well as the Ginchy Cross.

Bookroom

Bookroom

The four granite bookrooms, representing the four provinces of Ireland, contain the books of remembrance as well as the Ginchy Cross.

Bookroom

Bookroom

The four granite bookrooms, representing the four provinces of Ireland, contain the books of remembrance as well as the Ginchy Cross.

Fountain

Fountain

The obelisks at the centre of the broad-based fountains symbolise candles.

Fountain

Fountain

The obelisks at the centre of the broad-based fountains symbolise candles.

War Stone

War Stone

Weighing seven and a half tons, this is identical to First World War Stones found across the world, and resembles an altar.

Central Lawn

Central Lawn

The lawn enclosed by a high dry limestone wall with granite piers.

Great Cross

Great Cross

On the cope of the wall at the cross is inscribed the words “To the memory of the 49,400 Irishmen who gave their lives in the Great War, 1914-18”.

Pedestrian Gate

Pedestrian Gate